TS

leviscia

The race to save Peter Kassig

The American aid worker was killed by his Isis captors on 16 November. Here, for the first time, is the story of an extraordinary effort to secure his release, which involved a radical New York lawyer, the US government, and the world’s most revered jihadi scholar

On the evening of 3 October, the New York attorney Stanley Cohen got a phone call about Peter Kassig, the young American aid worker held hostage by Islamic State (Isis). The callers were Palestinians from the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon who knew Kassig, and they were “very upset”, Cohen recalled. They had just seen the footage of Alan Henning, a British hostage, being beheaded. At the end of the video, when the masked terrorist who has been dubbed “Jihadi John” paraded another hostage before the camera, they recognised their friend Peter.

Kassig had done relief and medical work in Sabra and Shatila, and even helped raise money for the refugees, before he was kidnapped in October 2013. “He’s a good guy,” the callers told Cohen. Given the pace of previous Isis executions – roughly once a fortnight since August – they feared Kassig might have only two weeks left to live. They were desperate to save him, and thought that Cohen would have contacts among militants in the region who could lobby for Kassig’s release.

Cohen is one of America’s most controversial lawyers: he has spent the past three decades defending clients that others found indefensible: Weather Underground radicals, Black Bloc anarchists, Hamas operatives. (“The entire Hamas leadership,” Cohen says, “are friends of mine and have been for years.”) Cohen was the defence lawyer for Osama bin Laden’s son-in-law, Suleiman Abu Ghaith – the highest-ranking al-Qaida figure to face trial in a US federal court since the 9/11 attacks – who was sentenced to life in prison in September.

Without giving it much thought, Cohen let the callers down gently: he had never dealt with Isis before, and there wasn’t much he could do for Kassig. Besides, he had other things on his mind. After pleading guilty to failing to file tax returns and obstructing the US Internal Revenue Service, Cohen is going to prison next month to serve an 18-month sentence. He believes that the IRS has been hounding him – “for seven solid years” – because of his controversial clients. “It never fucking ends,” he said. “$600,000 in legal fees … $100,000 in accounting fees, rumours, subpoenas, interrogatories.” In April, he decided to plead guilty to put a stop to it all. “I finally made the decision,” he said, “I’ll go to jail and do [legal] work for prisoners. I don’t give a shit.”

A few days later, as he returned from court to the plant-filled loft in Manhattan’s East Village that serves as his home and office, Cohen got another phone call. It was his old friend John Penley – a photojournalist, activist and navy veteran, who sometimes worked with the group Veterans for Peace. “From nowhere,” Cohen recalled, “he says, ‘Would you make a public statement on behalf of Peter Kassig?’” Penley later explained that he had reached out to Cohen because Kassig was a fellow veteran – he served as an army ranger in Iraq in 2007 but was later given a medical discharge – and Penley thought “there was a chance to save his life”.

To Cohen, it seemed like fate. “Here’s two calls within a week,” he said. He told Penley he would see what he could do, and asked his assistant to compile a dossier on Kassig, which included an interview he’d given to Time magazine before his capture, about his humanitarian work with Syrian refugees. As he leafed through the documents, Cohen saw something of himself – and the young activists he’d defended over the years – in Kassig. “I was thinking, if I was 25 or 26 in this day and age, I’d be in refugee camps in the Middle East,” Cohen recalled. “And that might easily be me as a hostage.”

But what really spurred Cohen into action was a letter Kassig had written to his parents in Indiana while in captivity, which they had released to the media a few days earlier. (Kassig’s parents chose not to comment on this story.) In the weeks to come, as Cohen flew to Kuwait and then Jordan in an audacious bid to negotiate Kassig’s release, he thought often of the letter’s heartbreaking final paragraph:

“I read those words and I started to well up,” Cohen said. That’s when he picked up the phone, called his best jihadist contact, and launched an improbable series of back-channel talks – reported here for the first time – in which Cohen, with the encouragement of the FBI, persuaded senior clerics and former fighters aligned with al-Qaida to open negotiations with Isis in an attempt to save the life of an American hostage.

* * *

The man Cohen called was a Kuwaiti member of al-Qaida, a veteran of the Afghanistan war and former Guantánamo detainee, who had helped him contact senior al-Qaida figures when he was building the case for the defence in the trial of Bin Laden’s son-in-law, Abu Ghaith. In the process, the two had become “very close”, Cohen said. (For security reasons, the Guardian is not disclosing his identity.) Cohen and his translator came to refer to the Kuwaiti as “Food”, because whenever they met him, dishes piled with steaming meat, lobster, grilled fish, and shrimp were served.

Cohen has spent a lifetime negotiating on high-profile cases, but the operation to free Kassig was something new for him. When Cohen deals with the US government in the courtroom or phones up Hezbollah, there is always a clear process. Even if the clock is ticking, as in a death row case, “you know if this person says this is the deal, that’s the deal”, he said. With Isis, Cohen didn’t even know where to begin. All he knew was that he had to create a channel to the group’s leadership.

On the phone, “Food” told Cohen he had recently been involved in successful hostage negotiations with the second largest Islamist rebel group in Syria, the al-Nusra Front. In September, he had helped secure the unilateral release of 45 Fijian UN peacekeepers who had been captured in the Golan Heights two weeks earlier. Cohen asked Food what he thought about Kassig’s situation. The reply was terse: “He’s gonna die.”

At this point, Cohen tentatively laid out his plan. The US wasn’t going to pay a ransom or agree to a prisoner swap, and they weren’t going to stop bombing Isis, as Jihadi John demanded. But maybe there was another way of persuading them to release the American. Instead of trading lives for money, Cohen suggested that Isis could dedicate Kassig’s release to Muslim political prisoners around the world, including those in Guantánamo. “You make political gestures that are more powerful than six million dollars,” Cohen explained. Food, who was no fan of Isis, paused, and then said he liked the plan but that he would have to consult a few people about it. The next day, he rang Cohen and said: “We’d like to save this guy.”

The “we” referred to a loose collective of Food’s allies in Kuwait – which included a few fellow ex-mujahideen fighters, but also some academics, doctors, and Salafist clerics, at least one of whom is named as a terrorist on a US sanctions list. Cohen described them as “older guys who’ve been around” – veterans of al-Qaida and Afghanistan, whose strategic outlook had evolved over time. Though they despised the west, they’d come to appreciate what could be achieved through politics rather than violence, Cohen said. They made decisions by consensus, and according to Cohen, always framed discussions in terms of “we have met, we’ve collectively decided certain things, we’ve got to get back to people; folks are of the opinion, people believe.” Cohen called them “the Food group”.

The Food group hated Isis, which they believed was harming Islam and helping justify foreign interventions by the US and its client states – Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt. They also cared about Kassig’s fate. He converted to Islam and had taken the name Abdul-Rahman during his year in captivity. This, they thought, made the idea of executing him particularly heinous. But despite these profound disagreements with Isis, they had strong ties to the group and with one Isis “cabinet member” in particular. They were Cohen’s only route to Kassig.

Food told Cohen that he couldn’t conduct complex talks over the phone. Cohen would have to fly to Kuwait. Cohen agreed, but before he hung up, he asked Food one last question – the same question he’d ask almost every day for the next five weeks: “Is Kassig still alive?”

“I checked on it,” Food replied. “He’s alive.”

* * *

Now that he had opened a possible channel to Isis, Cohen knew he would have to bring US officials on side. He foresaw a point sooner or later when he might need officials to help him clear potential diplomatic roadblocks. He was also concerned that without official sanction, he might be arrested. But reaching out to the US government was a big step for Cohen – he said it was the first time he’d ever felt “on the same page” as his lifelong antagonists. He quickly contacted a US official he thought he could trust, a federal prosecutor who Cohen had battled in court but come to respect. “I think he’s got a pretty good idea of who I am, why I am,” Cohen recalled. “I basically told him everything.” That included, with Food’s permission, revealing who he had been communicating with.

Stanley Cohen, lawyer, in his New York City apartment. Photograph: Tim Knox

The two lawyers knew that they needed to act quickly – it had already been a week since Isis had released footage of Alan Henning’s execution. On 10 October, just hours after they had first spoken, the prosecutor put Cohen in touch with an FBI counterterrorism official at the Washington field office, which deals with international hostage rescue. (The FBI has requested that the Guardian not identify the official, who we will call “Mike” – not his real name.) Cohen had dealt with a lot of FBI agents over the years, but he found that he liked Mike. Although Cohen saw Mike as a “true believer” – an American patriot – he said the FBI agent understood that it was sometimes necessary to talk with the most hated of enemies.

Between 10 and 12 October, the three engaged in a rapid series of conference calls – Cohen at his home, the FBI official in Washington, and the federal prosecutor at his offices. Together they went through the tentative proposal for Kassig’s unilateral release and hammered out the terms of engagement. Mike repeatedly reminded Cohen that he would be travelling as a private citizen and was not at liberty to promise anything from the US in return for Kassig’s freedom. In turn, Cohen explained that the last thing he wanted to be was a representative of the US government. He would work transparently, Cohen said, but he would not be monitored and refused in advance to give debriefings on his contacts. His job, he said, was to feel the situation out, “build bridges” and put a process together to reach Kassig’s captors.

Cohen’s other demands were simple. First, he needed a translator. The government officials were happy for him to use Marwan Abdel-Rahman, a court-certified Arabic translator who had worked with Cohen before. (Abdel-Rahman kept notes during the process, and spoke to the Guardian extensively about the events recounted in this article.) Second, Cohen needed the FBI to pick up the tab for hotels and flights. That was it, he says. “[There was] no debate – [it was like] ‘what are you talking about, $20,000 to save someone’s life?’”. The Guardian has seen receipts and forms filed by Cohen and sent to the FBI totalling $24,239.

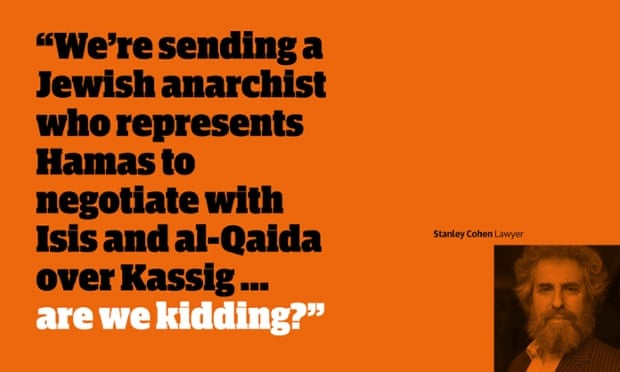

Not everyone was happy that Cohen – who had just pleaded guilty to a felony – would be leading US efforts to free Kassig. But the US didn’t have many back channels with Isis that they could exploit in situations like these. “There was apparently some white boy from Princeton – I assume from the State Department or Department of Justice – who quipped, ‘We’re sending a Jewish anarchist lawyer who represents Hamas to the Middle East to negotiate with Isis and al-Qaida over Kassig?’,” Cohen says. “And apparently some serious true believer responded, ‘Who the fuck else would we send?’”

Cohen had his allies in place. Four days after the phone call from Penley, on the evening of Monday 13 October, he and Abdel-Rahman were boarding a Kuwait Airways flight out of JFK.

* * *

When Cohen and Abdel-Rahman arrived in Kuwait, they didn’t know what they’d be dealing with. All they had was a commitment that Kassig would remain alive while Cohen was still engaged on the ground. “They [Isis] want a discussion,” Food had told him. On 15 October, Cohen checked into the Jumeirah hotel – a place he prefers to most Kuwaiti hotels because he feels safe there. Most of the clientele are Arabs and the perimeter is well guarded. “It’s not,” he says, “the kind of place you’re going to disappear from.”

Over the next two days, Food took the lead, helping to organise meetings in Cohen’s hotel room, the dining area, and at people’s houses. Cohen met a number of al-Qaida veterans and radical clerics. In these meetings, they ate a lot of food, drank a lot of coffee, and talked politics. The conversation would often drift; Cohen occasionally caught Abdel-Rahman rolling his eyes as clerics droned on for hours about seemingly irrelevant topics, such as the failure of Nasserite movements in the Middle East. But this is the nature of negotiation, says Cohen. “I may have to spend four hours talking about abstract issues until I get to that one important sentence.” On more than one occasion, Cohen said he had to drag conversations back to Kassig.

On 17 October, Food told Cohen that after speaking to an Isis cabinet member and various warlords on the ground, he and his associates in Kuwait had decided that the only way to save Kassig was to reach out to Isis’s chief scholar, a 30-year-old Bahraini called Turki al-Binali. The young cleric was the only person who could stay Jihadi John’s knife with a single edict. And the only way to get to Binali was through his former teacher, the Jordanian Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, who may be the world’s most revered living jihadi scholar. Maqdisi and Binali had fallen out over Isis’s theological legitimacy. If Cohen was going to save Kassig, he realised this dispute would have to be resolved as well.

Maqdisi is a slightly rumpled, middle-aged theologian, but his religious fatwas have influenced a generation of jihadis around the world, who have seized upon his writings as a theological justification for violence. One of Maqdisi’s most famous acolytes was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who, as leader of al-Qaida in Iraq, carried out a notoriously bloody campaign of beheadings and bombings that targeted hotels, UN offices and Shia holy places. After Zarqawi was killed by a US airstrike in 2006, his group evolved into the Islamic State in Iraq, and then Isis.

Radical Muslim cleric Abu Qatada (right) listens to Islamist scholar Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi during a celebration after his release from prison on 24 September. Photograph: Majed Jaber/Reuters

But even before the creation of Isis, Maqdisi was horrified by Zarqawi’s actions, particularly the casual slaughter of lay Shia. He believed Zarqawi had misinterpreted his teachings. This division between soldiers and scholars – between those who write the books and those who fire the bullets – has never raged so violently within the Salafist jihadi movement as it does today. This July, Maqdisi described Isis as “deviant” and rejected the legitimacy of the caliphate. He’s been supported by a friend who is another big player in this ideological conflict, Abu Qatada, a Palestinian Jordanian who lived in London for 20 years until the UK government finally managed to deport him to Jordan last year to face charges for plotting terror attacks on Americans and Israelis in Jordan in 1998 and 1999.

Like Maqdisi, Abu Qatada despises Isis. Speaking to a major western news outlet for the first time since his acquittal on terrorism charges in Jordan this summer, he told the Guardian: “What these people don’t understand is that I’ve been in this area [the Salafist sphere] for over 30 years. Our role, as Salafists … is to ignite the revolution and create the conditions to bring down the dictatorial regimes and then let others who are more qualified to take over power.

On the evening of 3 October, the New York attorney Stanley Cohen got a phone call about Peter Kassig, the young American aid worker held hostage by Islamic State (Isis). The callers were Palestinians from the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon who knew Kassig, and they were “very upset”, Cohen recalled. They had just seen the footage of Alan Henning, a British hostage, being beheaded. At the end of the video, when the masked terrorist who has been dubbed “Jihadi John” paraded another hostage before the camera, they recognised their friend Peter.

Kassig had done relief and medical work in Sabra and Shatila, and even helped raise money for the refugees, before he was kidnapped in October 2013. “He’s a good guy,” the callers told Cohen. Given the pace of previous Isis executions – roughly once a fortnight since August – they feared Kassig might have only two weeks left to live. They were desperate to save him, and thought that Cohen would have contacts among militants in the region who could lobby for Kassig’s release.

Cohen is one of America’s most controversial lawyers: he has spent the past three decades defending clients that others found indefensible: Weather Underground radicals, Black Bloc anarchists, Hamas operatives. (“The entire Hamas leadership,” Cohen says, “are friends of mine and have been for years.”) Cohen was the defence lawyer for Osama bin Laden’s son-in-law, Suleiman Abu Ghaith – the highest-ranking al-Qaida figure to face trial in a US federal court since the 9/11 attacks – who was sentenced to life in prison in September.

Without giving it much thought, Cohen let the callers down gently: he had never dealt with Isis before, and there wasn’t much he could do for Kassig. Besides, he had other things on his mind. After pleading guilty to failing to file tax returns and obstructing the US Internal Revenue Service, Cohen is going to prison next month to serve an 18-month sentence. He believes that the IRS has been hounding him – “for seven solid years” – because of his controversial clients. “It never fucking ends,” he said. “$600,000 in legal fees … $100,000 in accounting fees, rumours, subpoenas, interrogatories.” In April, he decided to plead guilty to put a stop to it all. “I finally made the decision,” he said, “I’ll go to jail and do [legal] work for prisoners. I don’t give a shit.”

A few days later, as he returned from court to the plant-filled loft in Manhattan’s East Village that serves as his home and office, Cohen got another phone call. It was his old friend John Penley – a photojournalist, activist and navy veteran, who sometimes worked with the group Veterans for Peace. “From nowhere,” Cohen recalled, “he says, ‘Would you make a public statement on behalf of Peter Kassig?’” Penley later explained that he had reached out to Cohen because Kassig was a fellow veteran – he served as an army ranger in Iraq in 2007 but was later given a medical discharge – and Penley thought “there was a chance to save his life”.

To Cohen, it seemed like fate. “Here’s two calls within a week,” he said. He told Penley he would see what he could do, and asked his assistant to compile a dossier on Kassig, which included an interview he’d given to Time magazine before his capture, about his humanitarian work with Syrian refugees. As he leafed through the documents, Cohen saw something of himself – and the young activists he’d defended over the years – in Kassig. “I was thinking, if I was 25 or 26 in this day and age, I’d be in refugee camps in the Middle East,” Cohen recalled. “And that might easily be me as a hostage.”

But what really spurred Cohen into action was a letter Kassig had written to his parents in Indiana while in captivity, which they had released to the media a few days earlier. (Kassig’s parents chose not to comment on this story.) In the weeks to come, as Cohen flew to Kuwait and then Jordan in an audacious bid to negotiate Kassig’s release, he thought often of the letter’s heartbreaking final paragraph:

Quote:

“I read those words and I started to well up,” Cohen said. That’s when he picked up the phone, called his best jihadist contact, and launched an improbable series of back-channel talks – reported here for the first time – in which Cohen, with the encouragement of the FBI, persuaded senior clerics and former fighters aligned with al-Qaida to open negotiations with Isis in an attempt to save the life of an American hostage.

* * *

The man Cohen called was a Kuwaiti member of al-Qaida, a veteran of the Afghanistan war and former Guantánamo detainee, who had helped him contact senior al-Qaida figures when he was building the case for the defence in the trial of Bin Laden’s son-in-law, Abu Ghaith. In the process, the two had become “very close”, Cohen said. (For security reasons, the Guardian is not disclosing his identity.) Cohen and his translator came to refer to the Kuwaiti as “Food”, because whenever they met him, dishes piled with steaming meat, lobster, grilled fish, and shrimp were served.

Cohen has spent a lifetime negotiating on high-profile cases, but the operation to free Kassig was something new for him. When Cohen deals with the US government in the courtroom or phones up Hezbollah, there is always a clear process. Even if the clock is ticking, as in a death row case, “you know if this person says this is the deal, that’s the deal”, he said. With Isis, Cohen didn’t even know where to begin. All he knew was that he had to create a channel to the group’s leadership.

On the phone, “Food” told Cohen he had recently been involved in successful hostage negotiations with the second largest Islamist rebel group in Syria, the al-Nusra Front. In September, he had helped secure the unilateral release of 45 Fijian UN peacekeepers who had been captured in the Golan Heights two weeks earlier. Cohen asked Food what he thought about Kassig’s situation. The reply was terse: “He’s gonna die.”

At this point, Cohen tentatively laid out his plan. The US wasn’t going to pay a ransom or agree to a prisoner swap, and they weren’t going to stop bombing Isis, as Jihadi John demanded. But maybe there was another way of persuading them to release the American. Instead of trading lives for money, Cohen suggested that Isis could dedicate Kassig’s release to Muslim political prisoners around the world, including those in Guantánamo. “You make political gestures that are more powerful than six million dollars,” Cohen explained. Food, who was no fan of Isis, paused, and then said he liked the plan but that he would have to consult a few people about it. The next day, he rang Cohen and said: “We’d like to save this guy.”

The “we” referred to a loose collective of Food’s allies in Kuwait – which included a few fellow ex-mujahideen fighters, but also some academics, doctors, and Salafist clerics, at least one of whom is named as a terrorist on a US sanctions list. Cohen described them as “older guys who’ve been around” – veterans of al-Qaida and Afghanistan, whose strategic outlook had evolved over time. Though they despised the west, they’d come to appreciate what could be achieved through politics rather than violence, Cohen said. They made decisions by consensus, and according to Cohen, always framed discussions in terms of “we have met, we’ve collectively decided certain things, we’ve got to get back to people; folks are of the opinion, people believe.” Cohen called them “the Food group”.

The Food group hated Isis, which they believed was harming Islam and helping justify foreign interventions by the US and its client states – Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt. They also cared about Kassig’s fate. He converted to Islam and had taken the name Abdul-Rahman during his year in captivity. This, they thought, made the idea of executing him particularly heinous. But despite these profound disagreements with Isis, they had strong ties to the group and with one Isis “cabinet member” in particular. They were Cohen’s only route to Kassig.

Food told Cohen that he couldn’t conduct complex talks over the phone. Cohen would have to fly to Kuwait. Cohen agreed, but before he hung up, he asked Food one last question – the same question he’d ask almost every day for the next five weeks: “Is Kassig still alive?”

“I checked on it,” Food replied. “He’s alive.”

* * *

Now that he had opened a possible channel to Isis, Cohen knew he would have to bring US officials on side. He foresaw a point sooner or later when he might need officials to help him clear potential diplomatic roadblocks. He was also concerned that without official sanction, he might be arrested. But reaching out to the US government was a big step for Cohen – he said it was the first time he’d ever felt “on the same page” as his lifelong antagonists. He quickly contacted a US official he thought he could trust, a federal prosecutor who Cohen had battled in court but come to respect. “I think he’s got a pretty good idea of who I am, why I am,” Cohen recalled. “I basically told him everything.” That included, with Food’s permission, revealing who he had been communicating with.

Stanley Cohen, lawyer, in his New York City apartment. Photograph: Tim Knox

The two lawyers knew that they needed to act quickly – it had already been a week since Isis had released footage of Alan Henning’s execution. On 10 October, just hours after they had first spoken, the prosecutor put Cohen in touch with an FBI counterterrorism official at the Washington field office, which deals with international hostage rescue. (The FBI has requested that the Guardian not identify the official, who we will call “Mike” – not his real name.) Cohen had dealt with a lot of FBI agents over the years, but he found that he liked Mike. Although Cohen saw Mike as a “true believer” – an American patriot – he said the FBI agent understood that it was sometimes necessary to talk with the most hated of enemies.

Between 10 and 12 October, the three engaged in a rapid series of conference calls – Cohen at his home, the FBI official in Washington, and the federal prosecutor at his offices. Together they went through the tentative proposal for Kassig’s unilateral release and hammered out the terms of engagement. Mike repeatedly reminded Cohen that he would be travelling as a private citizen and was not at liberty to promise anything from the US in return for Kassig’s freedom. In turn, Cohen explained that the last thing he wanted to be was a representative of the US government. He would work transparently, Cohen said, but he would not be monitored and refused in advance to give debriefings on his contacts. His job, he said, was to feel the situation out, “build bridges” and put a process together to reach Kassig’s captors.

Cohen’s other demands were simple. First, he needed a translator. The government officials were happy for him to use Marwan Abdel-Rahman, a court-certified Arabic translator who had worked with Cohen before. (Abdel-Rahman kept notes during the process, and spoke to the Guardian extensively about the events recounted in this article.) Second, Cohen needed the FBI to pick up the tab for hotels and flights. That was it, he says. “[There was] no debate – [it was like] ‘what are you talking about, $20,000 to save someone’s life?’”. The Guardian has seen receipts and forms filed by Cohen and sent to the FBI totalling $24,239.

Not everyone was happy that Cohen – who had just pleaded guilty to a felony – would be leading US efforts to free Kassig. But the US didn’t have many back channels with Isis that they could exploit in situations like these. “There was apparently some white boy from Princeton – I assume from the State Department or Department of Justice – who quipped, ‘We’re sending a Jewish anarchist lawyer who represents Hamas to the Middle East to negotiate with Isis and al-Qaida over Kassig?’,” Cohen says. “And apparently some serious true believer responded, ‘Who the fuck else would we send?’”

Cohen had his allies in place. Four days after the phone call from Penley, on the evening of Monday 13 October, he and Abdel-Rahman were boarding a Kuwait Airways flight out of JFK.

* * *

When Cohen and Abdel-Rahman arrived in Kuwait, they didn’t know what they’d be dealing with. All they had was a commitment that Kassig would remain alive while Cohen was still engaged on the ground. “They [Isis] want a discussion,” Food had told him. On 15 October, Cohen checked into the Jumeirah hotel – a place he prefers to most Kuwaiti hotels because he feels safe there. Most of the clientele are Arabs and the perimeter is well guarded. “It’s not,” he says, “the kind of place you’re going to disappear from.”

Over the next two days, Food took the lead, helping to organise meetings in Cohen’s hotel room, the dining area, and at people’s houses. Cohen met a number of al-Qaida veterans and radical clerics. In these meetings, they ate a lot of food, drank a lot of coffee, and talked politics. The conversation would often drift; Cohen occasionally caught Abdel-Rahman rolling his eyes as clerics droned on for hours about seemingly irrelevant topics, such as the failure of Nasserite movements in the Middle East. But this is the nature of negotiation, says Cohen. “I may have to spend four hours talking about abstract issues until I get to that one important sentence.” On more than one occasion, Cohen said he had to drag conversations back to Kassig.

On 17 October, Food told Cohen that after speaking to an Isis cabinet member and various warlords on the ground, he and his associates in Kuwait had decided that the only way to save Kassig was to reach out to Isis’s chief scholar, a 30-year-old Bahraini called Turki al-Binali. The young cleric was the only person who could stay Jihadi John’s knife with a single edict. And the only way to get to Binali was through his former teacher, the Jordanian Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, who may be the world’s most revered living jihadi scholar. Maqdisi and Binali had fallen out over Isis’s theological legitimacy. If Cohen was going to save Kassig, he realised this dispute would have to be resolved as well.

Maqdisi is a slightly rumpled, middle-aged theologian, but his religious fatwas have influenced a generation of jihadis around the world, who have seized upon his writings as a theological justification for violence. One of Maqdisi’s most famous acolytes was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who, as leader of al-Qaida in Iraq, carried out a notoriously bloody campaign of beheadings and bombings that targeted hotels, UN offices and Shia holy places. After Zarqawi was killed by a US airstrike in 2006, his group evolved into the Islamic State in Iraq, and then Isis.

Radical Muslim cleric Abu Qatada (right) listens to Islamist scholar Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi during a celebration after his release from prison on 24 September. Photograph: Majed Jaber/Reuters

But even before the creation of Isis, Maqdisi was horrified by Zarqawi’s actions, particularly the casual slaughter of lay Shia. He believed Zarqawi had misinterpreted his teachings. This division between soldiers and scholars – between those who write the books and those who fire the bullets – has never raged so violently within the Salafist jihadi movement as it does today. This July, Maqdisi described Isis as “deviant” and rejected the legitimacy of the caliphate. He’s been supported by a friend who is another big player in this ideological conflict, Abu Qatada, a Palestinian Jordanian who lived in London for 20 years until the UK government finally managed to deport him to Jordan last year to face charges for plotting terror attacks on Americans and Israelis in Jordan in 1998 and 1999.

Like Maqdisi, Abu Qatada despises Isis. Speaking to a major western news outlet for the first time since his acquittal on terrorism charges in Jordan this summer, he told the Guardian: “What these people don’t understand is that I’ve been in this area [the Salafist sphere] for over 30 years. Our role, as Salafists … is to ignite the revolution and create the conditions to bring down the dictatorial regimes and then let others who are more qualified to take over power.

Diubah oleh leviscia 29-12-2014 23:48

0

2.4K

1

Thread Digembok

Urutan

Terbaru

Terlama

Thread Digembok

Komunitas Pilihan