- Beranda

- Komunitas

- Entertainment

- Help, Tips & Tutorial Music

How to Mix In-Ear Monitors

TS

sonynoise

How to Mix In-Ear Monitors

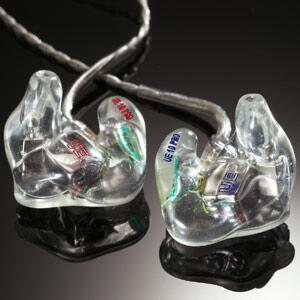

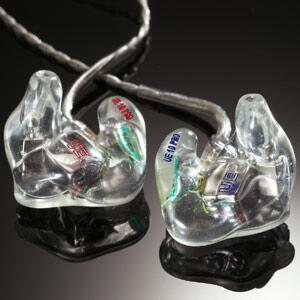

A few years ago, every big-name artist started the transition to in-ear monitors, even though the technology has been around since the early 1980s. It's been the "secret weapon" that has helped many artists perform better than they ever would have otherwise, and the love of in-ears has trickled down to independent musicians, too; heavy-hitters in the in-ear industry such as Future Sonics and Ultimate Ears have released superior quality universal earpieces featuring their expertly-designed sound signatures, and audio equipment companies such as Shure and Sennheiser have released affordable versions of their pro-quality (and pro-level-expensive) transmitter/receiver combos. It's never been easier to "go in-ear"; however, mixing in-ear monitors is a much different process than mixing wedges.

Whether you're on stage or in the studio, mixing in-ears is a much different affair than mixing wedge monitors.

In this guide, it's assumed that you're familiar with the equipment necessary for mixing in-ears, and you have a mixer and an in-ear system, either wired or wireless.

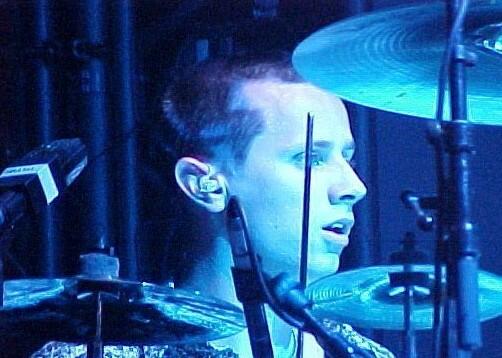

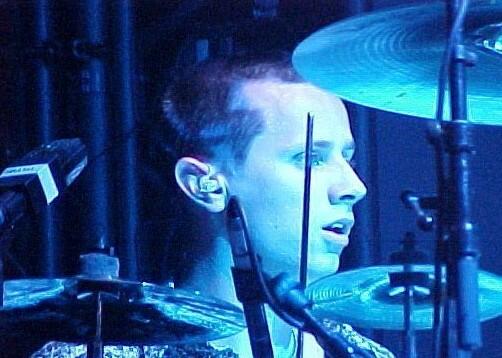

If you're a stationary musician (drummers, keyboard players, pedal steel players), a wired system is considered the best choice for both convenience and budget. For others, a wireless system of the highest quality you can afford is a great option. Also, don't forget the added cost of the monitor earpieces themselves; getting the best quality earpieces you can, whether custom-molded or universal-fit, is equally important. Many times, the included earphones with off-the-shelf systems offer relatively poor isolation and frequency response compared to even moderately-priced earphones purchased specifically for that purpose.

Hearing conservation:

The first thing to remember is that in-ear monitoring is all about hearing conservation as much as it is quality monitoring. Taking your monitors off the stage and into your ears presents an interesting problem; while in-ear monitors have the ability to offer greatly reduced sound pressure level (SPL) exposure, you can actually damage your hearing even worse with in-ears if done wrong. Remember, with wedge monitors, you have sometimes over 100 decibels of SPL coming at your head from several feet away; with in-ears, you could potentially push just as much relative SPL through speakers much closer to your ears.

In fact, many times touring sound companies -- while gladly providing top-quality in-ear monitoring equipment -- will refuse to provide an engineer for the artist, insisting that they supply their own, because nobody wants to be responsible for damaging a top artist's hearing with poorly executed in-ear mixes.

Many in-ear units offer fairly good limiters built into the beltpack, but it's never a bad idea to consider something external, especially if your artist is high-volume. The first part of your signal chain you should consider investing is a brick wall limiter for this very purpose. There are high end models -- such as the Aphex Dominator and DBX IEM processor -- but any quality limiter, such as those built into the relatively inexpensive DBX compressor/limiter combos, will work, especially when used in conjunction with built-in limiters. The purpose here isn't to compress or restrict the signal, but catch any unexpected feedback or transients from entering the earphone signal.

Stereo or mono?:

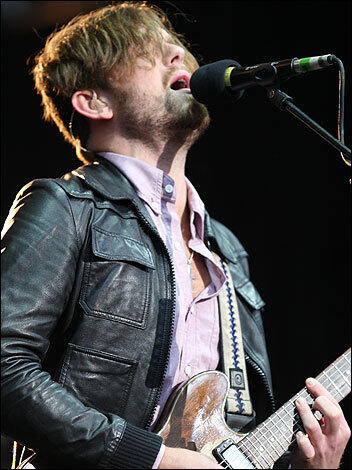

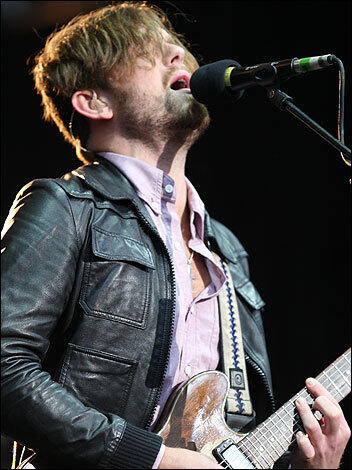

If you have the resources to run a stereo, or binaural, mix -- meaning, a stereo transmitter/receiver combo and a stereo auxillary send from your mixer -- then by all means, mix in stereo. Mixing in stereo has a distinct advantage on in-ears; you'll be able to set your mix in a way that mimics real life. If you're a lead singer, you'll want your vocals to be in the middle, but the guitars and drums can be panned around you just as you'd hear them while standing on stage.

Mono does have advantages. First, if you have a lower-end transmitter and receiver system, you will get a much stronger signal if you broadcast in mono. This is an advantage, especially in large cities where there are less clear frequencies to choose from.

Mono also has the advantage of being simple; if you don't have a stereo aux send, it's a lot easier to just use one instead of try to balance two separate sends as a stereo pair.

Mixing the mix:

The first thing to remember is that, while many artists that use in-ears prefer a full mix, on a small stage, this won't be necessary. Many times, you'll want a very simple mix on a smaller stage -- just vocals, a little guitar (or other instrument the mix owner is playing), and kick drum. Remember, the loudest sounds always win at the mic, so you'll get enough bleed from the vocal mics to hear everything else clearly.

On a larger stage, the sky's the limit. Just remember to communicate with your artist, and ask specifically what they want. If you're mixing in stereo, keep in mind that everything they want panned will be the opposite of what you see. If you see a guitar on the left side of the stage, they'll want it on the right side of their mix, because when they're facing the crowd, that's how they hear it.

Start with kick drum, overheads, and bass guitar. Once you get a solid foundation, you can add the vocals. Make sure that you avoid sending an effects send at this point -- make sure your artist is feeling comfortable just hearing the rhythm section and their own voice. Then, color in the rest of the instruments they require. Remember, they'll always want their own voice and their own instrument on top of everything else, so make sure you don't bury the important signals.

I tend to avoid putting snare or close-miced toms in a mix until the artist feels comfortable and asks for it. Sometimes, hearing a loud snare krack suddenly can be scary, and unnecessary to the overall health of the mix.

Adding ambience:

In a larger room, you'll soon find that your artist may feel isolated. This is very common; in-ears, by design, offer exceptional ambient noise reduction, which in turn can make a player feel cut off from the world around them.

First, consider adding a crowd microphone. Some like to put two on either side of the stage, in stereo, to give a wide sound; I prefer a single shotgun microphone at the base of the microphone stand in front of the lead singer, pointed at the back of the room. This gives a perfect "localization" -- the artist knows that the ambiance they hear is happening right at their feet.

Whether you're on stage or in the studio, mixing in-ears is a much different affair than mixing wedge monitors.

In this guide, it's assumed that you're familiar with the equipment necessary for mixing in-ears, and you have a mixer and an in-ear system, either wired or wireless.

If you're a stationary musician (drummers, keyboard players, pedal steel players), a wired system is considered the best choice for both convenience and budget. For others, a wireless system of the highest quality you can afford is a great option. Also, don't forget the added cost of the monitor earpieces themselves; getting the best quality earpieces you can, whether custom-molded or universal-fit, is equally important. Many times, the included earphones with off-the-shelf systems offer relatively poor isolation and frequency response compared to even moderately-priced earphones purchased specifically for that purpose.

Hearing conservation:

The first thing to remember is that in-ear monitoring is all about hearing conservation as much as it is quality monitoring. Taking your monitors off the stage and into your ears presents an interesting problem; while in-ear monitors have the ability to offer greatly reduced sound pressure level (SPL) exposure, you can actually damage your hearing even worse with in-ears if done wrong. Remember, with wedge monitors, you have sometimes over 100 decibels of SPL coming at your head from several feet away; with in-ears, you could potentially push just as much relative SPL through speakers much closer to your ears.

In fact, many times touring sound companies -- while gladly providing top-quality in-ear monitoring equipment -- will refuse to provide an engineer for the artist, insisting that they supply their own, because nobody wants to be responsible for damaging a top artist's hearing with poorly executed in-ear mixes.

Many in-ear units offer fairly good limiters built into the beltpack, but it's never a bad idea to consider something external, especially if your artist is high-volume. The first part of your signal chain you should consider investing is a brick wall limiter for this very purpose. There are high end models -- such as the Aphex Dominator and DBX IEM processor -- but any quality limiter, such as those built into the relatively inexpensive DBX compressor/limiter combos, will work, especially when used in conjunction with built-in limiters. The purpose here isn't to compress or restrict the signal, but catch any unexpected feedback or transients from entering the earphone signal.

Stereo or mono?:

If you have the resources to run a stereo, or binaural, mix -- meaning, a stereo transmitter/receiver combo and a stereo auxillary send from your mixer -- then by all means, mix in stereo. Mixing in stereo has a distinct advantage on in-ears; you'll be able to set your mix in a way that mimics real life. If you're a lead singer, you'll want your vocals to be in the middle, but the guitars and drums can be panned around you just as you'd hear them while standing on stage.

Mono does have advantages. First, if you have a lower-end transmitter and receiver system, you will get a much stronger signal if you broadcast in mono. This is an advantage, especially in large cities where there are less clear frequencies to choose from.

Mono also has the advantage of being simple; if you don't have a stereo aux send, it's a lot easier to just use one instead of try to balance two separate sends as a stereo pair.

Mixing the mix:

The first thing to remember is that, while many artists that use in-ears prefer a full mix, on a small stage, this won't be necessary. Many times, you'll want a very simple mix on a smaller stage -- just vocals, a little guitar (or other instrument the mix owner is playing), and kick drum. Remember, the loudest sounds always win at the mic, so you'll get enough bleed from the vocal mics to hear everything else clearly.

On a larger stage, the sky's the limit. Just remember to communicate with your artist, and ask specifically what they want. If you're mixing in stereo, keep in mind that everything they want panned will be the opposite of what you see. If you see a guitar on the left side of the stage, they'll want it on the right side of their mix, because when they're facing the crowd, that's how they hear it.

Start with kick drum, overheads, and bass guitar. Once you get a solid foundation, you can add the vocals. Make sure that you avoid sending an effects send at this point -- make sure your artist is feeling comfortable just hearing the rhythm section and their own voice. Then, color in the rest of the instruments they require. Remember, they'll always want their own voice and their own instrument on top of everything else, so make sure you don't bury the important signals.

I tend to avoid putting snare or close-miced toms in a mix until the artist feels comfortable and asks for it. Sometimes, hearing a loud snare krack suddenly can be scary, and unnecessary to the overall health of the mix.

Adding ambience:

In a larger room, you'll soon find that your artist may feel isolated. This is very common; in-ears, by design, offer exceptional ambient noise reduction, which in turn can make a player feel cut off from the world around them.

First, consider adding a crowd microphone. Some like to put two on either side of the stage, in stereo, to give a wide sound; I prefer a single shotgun microphone at the base of the microphone stand in front of the lead singer, pointed at the back of the room. This gives a perfect "localization" -- the artist knows that the ambiance they hear is happening right at their feet.

0

3.4K

4

Komentar yang asik ya

Urutan

Terbaru

Terlama

Komentar yang asik ya

Komunitas Pilihan