- Beranda

- Komunitas

- News

- Berita dan Politik

Indonesian Islamists’ pragmatic pivot in 2024

TS

DomCobbTotem

Indonesian Islamists’ pragmatic pivot in 2024

Quote:

Hardliners are adapting to electoral realities—and state restraints—in mobilising for Anies Baswedan

At the 2019 presidential election, Indonesia’s Islamist groups were at the peak of their influence. They banded together with Joko Widodo’s then rival, Prabowo Subianto, to orchestrate one of the most polarising presidential campaigns in Indonesia’s history. Though they have been battered by government repression since Widodo’s reelection in 2019, Islamist groups are now regrouping behind Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandarin the 2024 presidential race.

In the course of my doctoral research into Indonesia’s Islamist opposition movements in the Jokowi years, I have been following Islamist activists, both virtually and on the ground, as they campaign on behalf of Anies and Muhamin’s candidacy. I have been struck by how much more timid these Islamist groups’ campaign rhetoric is compared with 2019. Gone are the days when their volunteers would go around from house to house to spread internet-sourced propaganda accusing their political rival of being a Chinese communist agent who was bent on abolishing Islam from public life and was conspiring to assassinate Muslim leaders—things they said about Jokowi in 2019. They no longer describe the election in apocalyptic terms, where one candidate is portrayed as an evil force while the other is hailed as the saviour that could salvage Indonesia from impending doom.

Instead, Islamist activists in Anies’ team and from affiliated volunteer groups have chosen to emphasise his commitment to what they call “ethical politics” (an Islamist euphemism for governance based in Islamic morality), his concrete achievements as governor of Jakarta between 2017 and 2022, and his promise to restore the freedoms and justice that have been eroded under Jokowi. Islamists’ campaign style, in other words, has shifted from being one characterised by passionate ideological agitation to a more level-headed programmatic style, reflecting the overall decline in ideological polarisation during Jokowi’s second term.

But does that mean that Islamists have abandoned their ideological beliefs and goals, or does it simply reflect political expediency? I argue that Indonesian Islamists’ rhetorical moderation is primarily an adaptation to the three key political realities of the late Jokowi years.

Firstly, state repression has made Islamists cautious about embracing overtly sectarian campaigning. Secondly, with Islamists having aligned behind the candidacy of the Anies and Muhaimin, and keeping their options open with a reconciliation with Prabowo Subianto in a potential second round of the presidential election, they have sought not to alienate pluralist Muslim voters linked to traditionalist groups like Nahdlatul Ulama (NU).

Third, unlike in the aftermath of the mass mobilisations against the alleged blasphemy of former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, there isn’t a religiously-charged issue around which a dynamic of polarisation can arise. The issues of Rohingya and Israel–Palestine conflict have featured in the 2024 campaign, but these issues do not divide Indonesians neatly along Islamic–nationalist lines, and offer only limited potential for the reactivation of ideological passions in the short term.

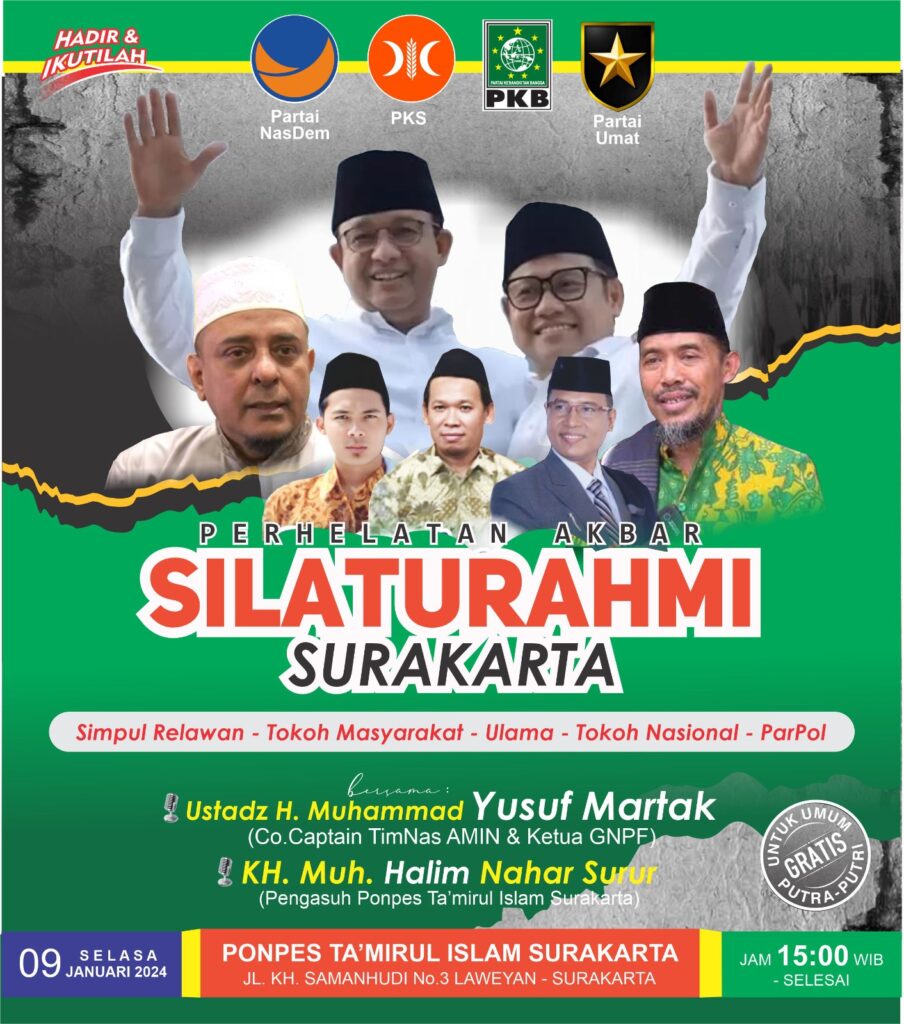

Promotional materials for a campaign event for Anies Baswedan featuring prominent Islamist cleric and “co-captain” of Anies’ campaign team, Yusuf Martak (left)

Promotional materials for a campaign event for Anies Baswedan featuring prominent Islamist cleric and “co-captain” of Anies’ campaign team, Yusuf Martak (left)De-risking religious rhetoric

I limit my analysis to non-violent Islamist groups such as FPI—relaunched, after the ban of the Front Pembela Islam/Islamic Defenders’ front in 2020, as the Front Persaudaraan Islam/Islamic Brotherhood Front—and the self-styled “Alumni” of the 212 movement activists that led the protests against former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama in 2016–17. These groups share relatively moderate goals and methods compared to jihadist extremists. They pursue an Islamisation of society and the state not via revolution but through gradualist tactics like proselytisation, education, social services, advocacy, and political participation. They will enthusiastically drum up intolerant sectarian sentiments (which they genuinely hold) when it benefits them, but remain ready to tone it down when their survival is at stake. For this community of non-jihadist Islamists, the goal is to win power first, then work on the religio-political reform later.

In 2024 as in 2019, direct engagement in electoral politics is part and parcel of this strategy. On 27 September 2023, Anies and Muhaimin visited the FPI leader Rizieq Shihab, as if to secure his blessing, just before they officially registered their candidacy. Once Anies’ candidacy was confirmed, he recruited Yusuf Martak, a close confidant of Rizieq, as one of the co-chairs of his success team.

Islamists have made it clear that they are not giving a blank cheque to Anies. In exchange for their support, they required Anies and Muhaimin to sign a 13-point “Integrity Pact” which, among other things, affirmed the candidates’ commitment to back the Islamist agenda of combatting secularism, communism, and religious blasphemy (for them, a code word for the perceived growth in the power and “arrogance” of Indonesia’s Christian minority). The agreement also stipulated that Anies and Muhaimin would enforce public morality based on Islamic norms and improve ordinary people’s economic circumstances by stopping a purported inflow of mainland Chinese workers.

Following the same formula as in 2019, in November 2023 FPI and its affiliates organised a Conference of Religious Scholars (Ijtima Ulama) in order to give their choice of candidate the stamp of religious authority. The 2023 Ijtima resulted in a religious recommendation by “Grand Imam” Rizieq Shihab to vote for Anies and his running mate Muhaimin. The idea is to leverage the grassroots network of FPI and the Brotherhood of 212 Alumni (Persaudaraan Alumni 212, or PA212) to organise campaign activities and the distribution of campaign materials in support of Anies. As of late 2023, the resurrected FPI boasted branches in 23 out of 38 provinces, while formal PA212 structures have been established in all districts in the 10 most populous provinces; both sped up their expansion of local branches with a view to mobilising voters for the 2024 election. That said, it is unclear how many members either organisation actually has—local FPI activists often double up as PA212 executives.

Although the “Integrity Pact” between FPI and the Anies campaign and the Ijtima Ulama’s endorsement of Anies exhibit some of the sectarian and xenophobic tone that characterised Islamist activism in the 2019 election, my on-the-ground observation of FPI-linked campaign events suggests they have cooled down their divisive religious narratives for 2024.

A typical campaign in Central Java, for instance, would attract between 50 to a few hundred people, though the number might be higher in FPI strongholds such as Banten and Greater Jakarta. Many such campaign events that I observed were simple (held in mosques, Islamic pesantren boarding schools, or other free venues) and mostly funded by volunteers and donations from local candidates seeking to win the sympathy of Islamist constituencies. Attendees at these events receive free T-shirts, posters, mugs and other merchandise, but I have not witnessed any exchange of monetary gifts (as has been reported in other candidates’ campaigns). This is not surprising given Anies has reported the lowest amount of campaign funds among the three presidential candidates.

What was more striking to me was the relative lack of religious zeal and apocalyptic narratives that were ubiquitous in 2019. Speaking at a pro-Anies volunteers meeting in Solo on 9 January, the secretary general of PA212 Uus Solihuddin told the volunteers to de-emphasise lofty ideology and focus more on concrete programmatic policies. Whereas in the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election Islamist leaders relied on intimidation and fear-mongering to coerce Muslims to vote for Anies (such as threatening to not perform funeral prayers for recently deceased Muslims who supported “infidel” candidates), Islamists are now carefully avoiding any statements that can be construed as smear campaign, misinformation or sectarian incitement. As PA212’s secretary-general instructed the assembled volunteers,

Stay clear of black campaigns! Focus on promoting the vision and mission of Amin (Anies and Muhaimin), make it viral by using plain, easily accessible language. Don’t talk about lofty ideas. Just talk about cheap groceries (sembako).Because let’s face it, most Indonesian people are not at that [intellectual] level yet. Engage the people by saying things like: do you want better healthcare? Do you want cheap electricity? Do you want a driver’s license that applies for a lifetime—no need to renew it every five years? Then you can reinforce the message by telling them that these are the recommendations of our ulama who have signed an agreement with Anies.

The caution around “black campaigns” reflects Islamists’ fear of persecution and arrest, a critical factor that explains the shift away from sectarian narratives. (Alfian Tanjung, another Islamist cleric who was present at the meeting in Solo described here, had been imprisoned from 2017 to 2020 after being convicted of criminal defamation for calling Jokowi and PDI–P “lackeys” of the Indonesian Communist Party/PKI).

SAFEnet, an NGO that advocates for freedom of online expression, reported in 2022 that the arrest of opposition activists under Indonesia’s Electronic Information and Transactions Law (UU ITE) has increased by 26%; most were charges with defaming state officials and institutions. Islamists are arguably the most targeted category of all opposition activists. The fact that Rizieq Shihab is on parole until June 2024, following his release from prison in July 2022, is a living reminder of the great risks they are facing: as one activist put it, “any tiny mistake could send Habib Rizieq back to prison, that’s why we need to be careful.”

Yusuf Martak similarly told a group of pro-Anies volunteers in Klaten and Solo that they should emphasise his concrete achievements in combating social ills in Jakarta, such as closing down a major brothel and a restaurant chain that gave free promotional beers to anyone named Muhammad. It was suggested that promoting his accomplishments in public morality and infrastructure development would be more effective and less risky than invoking overtly Islamist jargon (e.g. “infidels”, “shari’a”) that are closely associated with radicalism.

Maintaining moderate support

Last but not least, Islamists felt compelled to tone down their religious zeal in order to appease the moderate, traditionalist Muslim base of Anies’ running mate, Muhaimin Iskandar.

RELATE

Islamists were initially disappointed by the appointment of Muhaimin as Anies’ running mate because of his pluralist (NU) background, his implication in historical corruption cases, and his attendance at a 2023 Coldplay concert in Jakarta that was protested by FPI on the grounds that the band has shown support for LGBT people. Yet once Rizieq Shihab issued the instruction for the FPI rank and file to support Anies, they fell into line.

Many within Muhaimin’s NU milieu perceive Anies as a “Wahhabi”—a reference to the ultrapuritan brand of Sunni Islam associated with Saudi Arabia, which has become a slur among Muslim moderates in Indonesia—due to his modernist background and close relationship with the Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera/PKS). This is in the context of an internal rift within NU: the organisation’s chairman Yahya Cholil Staquf and most of its national board have sided with Prabowo, while influential NU kyai (traditionalist religious leaders), including NU’s former chair Said Aqil Siradj, have backed Muhaimin and his party PKB. In East Java, a number of kyai from Yahya’s camp exhorted their followers to not vote for Anies, saying that he secretly conspired with the banned transnational organisation Hizbut Tahrir and FPI to replace the Indonesian republic with a caliphate.

https://www.newmandala.org/indonesia...pivot-in-2024/

intinya gw baca2 ini, kaum radikal 2024 lbh jinak retorikanya dlm dukung abud karena takut brizieq masuk pnjara lg dan mereka plan loncat ke wowo di putaran kedua klo abud kalah,makanya penting 1 putaran buat prabowo . Mereka pgn meradikalisasi Indonesia jangka panjang, pelan2 pakai skola,pesantren atau jalur politik pake partai sapi. Intinya jangan pernah ksh kesempatan apinya membesar, 03 mau aliansi ama 01 malah bikin apinya membesar lg. menarik nih #asalbukan02 yg disuarakan buzzer2 di sini ga laku ama voter base 01 dan 03

03 yg minoritas dan abangan lbh pilih ke 02 klo 03 kalah

01 yg radikal dan islamis lbh pilih ke 02 juga klo 01 kalah krn mereka prnh dibantu wowo

bukan.bomat dan 8 lainnya memberi reputasi

5

200

Kutip

14

Balasan

Komentar yang asik ya

Urutan

Terbaru

Terlama

Komentar yang asik ya

Komunitas Pilihan