- Beranda

- Komunitas

- News

- Sejarah & Xenology

Mohenjo-Daro, Sebuah Kota Metropolis Kuno di Lembah Indus

TS

berita.medan

Mohenjo-Daro, Sebuah Kota Metropolis Kuno di Lembah Indus

Quote:

Mohenjo-daro, An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis

Mohenjo-daro is widely recognized as one of the most important early cities of South Asia and the Indus Civilization and yet most publications rarely provide more than a cursory overview of this important site.

There are several different spellings of the site name and in this article we have chosen to use the most common form, Mohenjo-daro (the Mound of Mohen or Mohan), though other spellings are equally valid: Mohanjo-daro (Mound of Mohan = Krishna), Moenjo-daro (Mound of the Dead), Mohenjo-daro, Mohenjodaro or even Mohen-jo-daro. Many publications still state that Mohenjo-daro is located in India (presumably referring to ancient India), but since the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the site has been under the protection of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan.

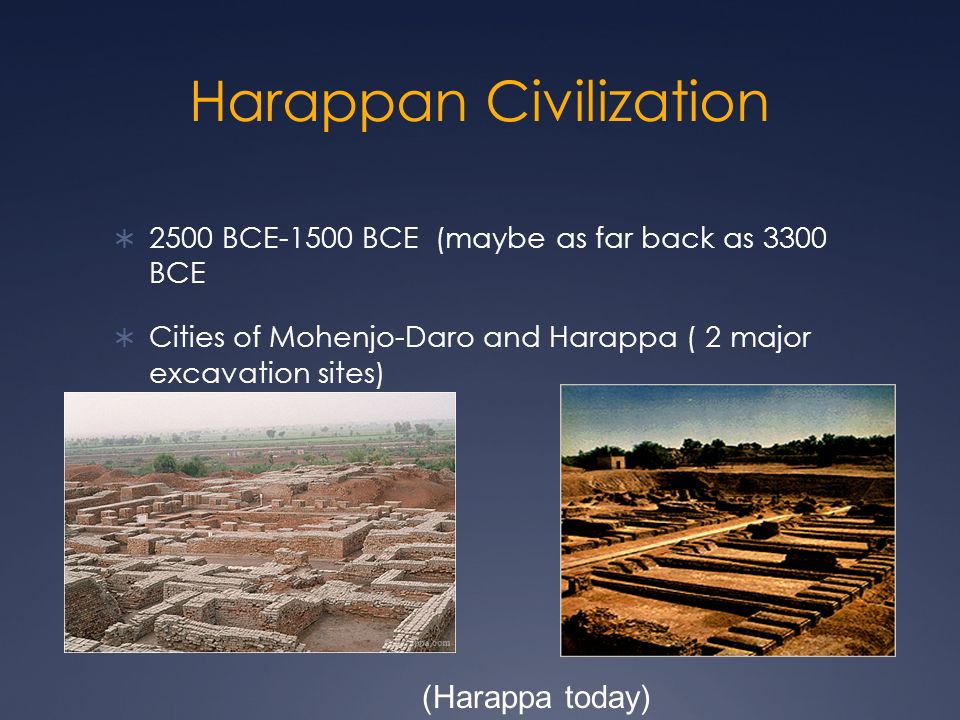

Discovery and Major Excavations

Mohenjo-daro was discovered in 1922 by R. D. Banerji, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India, two years after major excavations had begun at Harappa, some 590 km to the north. Large-scale excavations were carried out at the site under the direction of John Marshall, K. N. Dikshit, Ernest Mackay, and numerous other directors through the 1930s.

Although the earlier excavations were not conducted using stratigraphic approaches or with the types of recording techniques employed by modern archaeologists they did produce a remarkable amount of information that is still being studied by scholars today (see the Mohenjo-daro Bibliography).

The last major excavation project at the site was carried out by the late Dr. G. F. Dales in 1964-65, after which excavations were banned due to the problems of conserving the exposed structures from weathering.

Since 1964-65 only salvage excavation, surface surveys and conservation projects have been allowed at the site. Most of these salvage operations and conservation projects have been conducted by Pakistani archaeologists and conservators.

In the 1980's extensive architectural documentation, combined with detailed surface surveys, surface scraping and probing was done by German and Italian survey teams led by Dr. Michael Jansen (RWTH) and Dr. Maurizio Tosi (IsMEO).

The most extensive recent work at the site has focused on attempts at conservation of the standing structures undertaken by UNESCO in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, as well as various foreign consultants.

Details of the most recent salvage excavations and conservation are found in obscure journals or reports that are not readily available to the public, but are listed in the Bibliography for those interested in searching them out.

Media Source : https://www.harappa.com/mohenjo-daro...daroessay.html

Quote:

Mohenjo Daro : "Faceless" Indus Valley City Puzzles Archaeologists

By John Roach

A well-planned street grid and an elaborate drainage system hint that the occupants of the ancient Indus civilization city of Mohenjo Daro were skilled urban planners with a reverence for the control of water. But just who occupied the ancient city in modern-day Pakistan during the third millennium B.C. remains a puzzle.

"It's pretty faceless," says Indus expert Gregory Possehl of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

The city lacks ostentatious palaces, temples, or monuments. There's no obvious central seat of government or evidence of a king or queen. Modesty, order, and cleanliness were apparently preferred. Pottery and tools of copper and stone were standardized. Seals and weights suggest a system of tightly controlled trade.

The city's wealth and stature is evident in artifacts such as ivory, lapis, carnelian, and gold beads, as well as the baked-brick city structures themselves.

A watertight pool called the Great Bath, perched on top of a mound of dirt and held in place with walls of baked brick, is the closest structure Mohenjo Daro has to a temple. Possehl, a National Geographic grantee, says it suggests an ideology based on cleanliness.

Wells were found throughout the city, and nearly every house contained a bathing area and drainage system.

City of Mounds

Archaeologists first visited Mohenjo Daro in 1911. Several excavations occurred in the 1920s through 1931. Small probes took place in the 1930s, and subsequent digs occurred in 1950 and 1964.

The ancient city sits on elevated ground in the modern-day Larkana district of Sindh province in Pakistan.

During its heyday from about 2500 to 1900 B.C., the city was among the most important to the Indus civilization, Possehl says. It spread out over about 250 acres (100 hectares) on a series of mounds, and the Great Bath and an associated large building occupied the tallest mound.

According to University of Wisconsin, Madison, archaeologist Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, also a National Geographic grantee, the mounds grew organically over the centuries as people kept building platforms and walls for their houses.

"You have a high promontory on which people are living," he says.

With no evidence of kings or queens, Mohenjo Daro was likely governed as a city-state, perhaps by elected officials or elites from each of the mounds.

Prized Artifacts

A miniature bronze statuette of a nude female, known as the dancing girl, was celebrated by archaeologists when it was discovered in 1926, Kenoyer notes.

Of greater interest to him, though, are a few stone sculptures of seated male figures, such as the intricately carved and colored Priest King, so called even though there is no evidence he was a priest or king.

The sculptures were all found broken, Kenoyer says. "Whoever came in at the very end of the Indus period clearly didn't like the people who were representing themselves or their elders," he says.

Just what ended the Indus civilization—and Mohenjo Daro—is also a mystery.

Kenoyer suggests that the Indus River changed course, which would have hampered the local agricultural economy and the city's importance as a center of trade.

But no evidence exists that flooding destroyed the city, and the city wasn't totally abandoned, Kenoyer says. And, Possehl says, a changing river course doesn't explain the collapse of the entire Indus civilization. Throughout the valley, the culture changed, he says.

"It reaches some kind of obvious archaeological fruition about 1900 B.C.," he said. "What drives that, nobody knows."

Media Source : http://www.nationalgeographic.com/ar.../mohenjo-daro/

By John Roach

A well-planned street grid and an elaborate drainage system hint that the occupants of the ancient Indus civilization city of Mohenjo Daro were skilled urban planners with a reverence for the control of water. But just who occupied the ancient city in modern-day Pakistan during the third millennium B.C. remains a puzzle.

"It's pretty faceless," says Indus expert Gregory Possehl of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

The city lacks ostentatious palaces, temples, or monuments. There's no obvious central seat of government or evidence of a king or queen. Modesty, order, and cleanliness were apparently preferred. Pottery and tools of copper and stone were standardized. Seals and weights suggest a system of tightly controlled trade.

The city's wealth and stature is evident in artifacts such as ivory, lapis, carnelian, and gold beads, as well as the baked-brick city structures themselves.

A watertight pool called the Great Bath, perched on top of a mound of dirt and held in place with walls of baked brick, is the closest structure Mohenjo Daro has to a temple. Possehl, a National Geographic grantee, says it suggests an ideology based on cleanliness.

Wells were found throughout the city, and nearly every house contained a bathing area and drainage system.

City of Mounds

Archaeologists first visited Mohenjo Daro in 1911. Several excavations occurred in the 1920s through 1931. Small probes took place in the 1930s, and subsequent digs occurred in 1950 and 1964.

The ancient city sits on elevated ground in the modern-day Larkana district of Sindh province in Pakistan.

During its heyday from about 2500 to 1900 B.C., the city was among the most important to the Indus civilization, Possehl says. It spread out over about 250 acres (100 hectares) on a series of mounds, and the Great Bath and an associated large building occupied the tallest mound.

According to University of Wisconsin, Madison, archaeologist Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, also a National Geographic grantee, the mounds grew organically over the centuries as people kept building platforms and walls for their houses.

"You have a high promontory on which people are living," he says.

With no evidence of kings or queens, Mohenjo Daro was likely governed as a city-state, perhaps by elected officials or elites from each of the mounds.

Prized Artifacts

A miniature bronze statuette of a nude female, known as the dancing girl, was celebrated by archaeologists when it was discovered in 1926, Kenoyer notes.

Of greater interest to him, though, are a few stone sculptures of seated male figures, such as the intricately carved and colored Priest King, so called even though there is no evidence he was a priest or king.

The sculptures were all found broken, Kenoyer says. "Whoever came in at the very end of the Indus period clearly didn't like the people who were representing themselves or their elders," he says.

Just what ended the Indus civilization—and Mohenjo Daro—is also a mystery.

Kenoyer suggests that the Indus River changed course, which would have hampered the local agricultural economy and the city's importance as a center of trade.

But no evidence exists that flooding destroyed the city, and the city wasn't totally abandoned, Kenoyer says. And, Possehl says, a changing river course doesn't explain the collapse of the entire Indus civilization. Throughout the valley, the culture changed, he says.

"It reaches some kind of obvious archaeological fruition about 1900 B.C.," he said. "What drives that, nobody knows."

Media Source : http://www.nationalgeographic.com/ar.../mohenjo-daro/

Quote:

The Mohenjo Daro : Massacre

In the 1920s, the discovery of ancient cities at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa in Pakistan gave the first clue to the existence more than 4,000 years ago of a civilization in the Indus Valley to rival those known in Egypt and Mesopotamia. These cities demonstrated an exceptional level of civic planning and amenities. The houses were furnished with brick-built bathrooms and many had toilets. Wastewater from these was led into well-built brick sewers that ran along the centre of the streets, covered with bricks or stone slabs. Cisterns and wells finely constructed of wedge-shaped bricks held public supplies of drinking water. Mohenjo Daro also boasted a Great Bath on the high mound (citadel) overlooking the residential area of the city. Built of layers of carefully fitted bricks, gypsum mortar and waterproof bitumen, this basin is generally thought to have been used for ritual purification.

However, in contrast to the well-appointed houses and clean streets, the uppermost levels at Mohenjo Daro contained squalid makeshift dwellings, a careless intermingling of residential and industrial activity and, most significantly, a series of more than 40 sprawled skeletons lying scattered in streets and houses.

Paul Bahn (2002) describes the scene:

Quote:

"in a room with a public well in one area of the city were found the skeletons of two individuals who appeared desperately to have been using their last scraps of energy to crawl up the stair leading from the room to the street; the tumbled remains of two others lay nearby. Elsewhere in the area the ‘strangely contorted’ and incomplete remains of nine individuals were found, possibly thrown into a rough pit. In a lane between two houses in another area, another six skeletons were loosely covered with earth."

Numerous other skeletons were found within layers of rubble, ash and debris, or lying in streets in contorted positions that suggested the agonies of violent death.

A Violent Massacre

The remains of these individuals led many archaeologists at the time to conclude that these people all died by violence. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who excavated at Mohenjo Daro in 1950s, believed they were victims of a single massacre and suggested that the Indus civilization, whose demise was unexplained, had fallen to an armed invasion by Indo-Aryans, nomadic newcomers from the northwest, who are thought to have settled in India during the second millennium BC. Wheeler claimed the remains belonged to individuals who were defining the city in its final hours. He was so convincing that this theory became the accepted version of the fate of the Indus civilization.

However, many of his claims simply did not add up. There was no evidence that the skeletons belonged to ‘defenders of the city’ as no weapons were found and the skeletons contained no evidence of violent injuries. Some archaeologists suggested that the influx of Indo-Aryan people occurred after the decline of the Indus civilization while others questioned whether an Indo-Aryan invasion of the subcontinent even took place at all.

Media Source : http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancie...massacre-00819

Diubah oleh berita.medan 10-08-2017 17:13

0

6.2K

Kutip

16

Balasan

Komentar yang asik ya

Urutan

Terbaru

Terlama

Komentar yang asik ya

Komunitas Pilihan