When Indonesians head to the polls next Wednesday for what is expected to be the world's biggest direct presidential election, 70 per cent of its 193 million registered voters are expected to cast their ballots in a single day.

Indonesia, the world's fourth most populous country, wears its hard-fought democracy with ease. I witnessed this during each of its previous three presidential elections - in 2004, 2009 and 2014 - and again in recent weeks as I journeyed across rural and urban Java - the country's main island - to speak to voters, understand their views, and gauge what their choices might be, come election day.

Direct presidential elections were first held in 2004, six years after student protests and mass riots in several cities ended the 32-year rule of Indonesia's authoritarian leader Suharto.

Until this year, polling for local councils, regional assemblies and the national parliament were held three months before the presidential election.

Generally, I have emerged largely optimistic from my on-the-ground, straw-poll research expeditions. Indonesians cherish the opportunity to vote; it's something they would not readily sacrifice. Whether in east, central or west Java, an island with a population of more than 140 million, I have met people eager to discuss the merits or failings of their leaders, and conscious of the responsibility they have to register their hopes and concerns at the ballot box.

Yet, over time, I have noticed that competitive politics increasingly divides the country socially, though not so obviously along class lines, as in Europe. In Indonesia the electoral divide is, alarmingly, along religious lines - between Muslims and non-Muslims.

The story of Indonesia's 2019 election is one of two countries.

In one, an aspiring, mostly urban middle class worries about the erosion of tolerance and diversity; in the other, growing numbers of pious and conservative Muslims, many of them educated in rural religious schools, want laws that put Indonesia on the road to Islamic statehood.

These divergent visions sit uneasily alongside each other, and when Indonesians go to the polls this time round,

those fearing the erosion of tolerance will largely vote for the incumbent Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, a former city mayor with a common touch and an unthreatening manner; those who want the country to veer towards Islamic statehood will vote for Prabowo Subianto, a gruff former special forces commander who fought and almost won the election against Jokowi in 2014.

I saw these two Indonesias two weeks before the election in the west Java capital of Bandung, where a gathering of nervous middle-class millennials at a modern sculpture park worried about the decay of diversity; and at an Islamic teaching complex not far away, where the conviction of disciplined faith had thousands of devotees hanging on to every word of charismatic preacher Abdullah Gymnastiar. After the preaching was over, AA Gym, as he is known, sat patiently on an elevated office chair while the faithful lined up for selfies or to kiss his hand.

Outside, a large poster for the Prabowo campaign portrayed the candidate and his running mate, Sandiaga Uno, against the image of hardline Islamist Rizieq Shihab who lives in exile in Saudi Arabia to avoid facing criminal charges under the Anti-Pornography Act (Rizieq is accused of sending explicit WhatsApp messages to a woman who is not his wife).

To enhance his appeal to the conservative Islamic groups, Prabowo promises to bring Rizieq home, and presumably the charges will go away too.

"They believe Prabowo will bring (Rizieq) back, but they don't understand the law in the country," said Asep waving towards Al Artoq school, which he claims has 4,000 followers from around the area.

Equally alarming is President Widodo's response, which has been to try to win support from the conservative Muslim quarters by choosing a conservative Muslim cleric as his running mate.

My findings in west Java suggest this strategy has not worked. Prabowo still draws strong support from the devout Muslim population of west Java, where he won over 40 per cent more votes than Jokowi in 2014.

What is worrying, though, since Jokowi is likely to win the election at the national level, is how much leverage the Muslim lobby will now have on the president during his second term.

This makes many Indonesians who support Jokowi feel uneasy.

"Why do state schools and offices need to have mosques?" asked a Muslim mother who claims that her Buddhist son was denied promotion because he wasn't a Muslim. She was attending a discussion for millennials led by the Minister of Religion Lukman Hakim at a modern sculpture gallery in a swanky north Bandung neighbourhood. Lukman's response, to explain that the constitution and a battery of laws guarantee religious freedom, did not sound convincing.

"What about the recent incident in Bantul? Where Muslim residents refused to accept that non-Muslims could live among them?" asked another member of the audience.

The flustered minister shrugged off the incident, arguing that dialogue helped to repair these "misunderstandings".

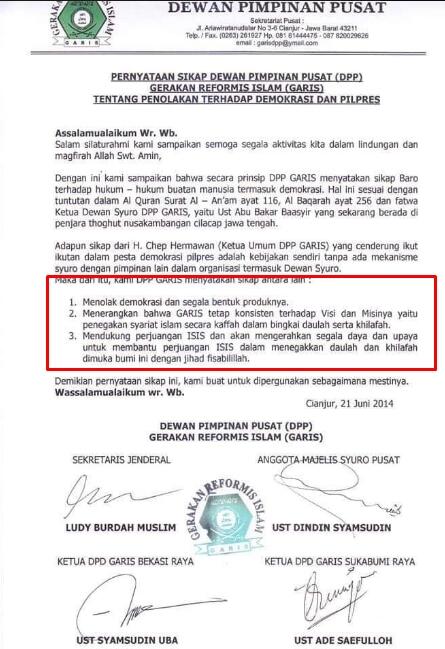

It is hard to misunderstand the signals that Prabowo's supporters are sending. At the rally in Ciamis, a group of young men mounted the stage shortly before the candidate arrived.

"We are the 'Two-One-Two mujahideen'," one of them cried. "Under our command, God willing, we will pursue our goal of the caliphate," one of the young men shouted. Two-One-Two refers to the broad coalition of conservative Islamic groups who mounted mass rallies at the end of 2017, forcing Jokowi's concession to demands to prosecute his former deputy on a charge of blasphemy.

In what many Indonesians consider a turning point for the country's respect for religious diversity, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, popularly known as Ahok, was accused of blasphemy after a doctored video was submitted as evidence that he was insulting the Koran. A court later sentenced him to two years in jail.

The crucible of this vision of Indonesia under Islamic law can be found a few kilometres down the road from Ciamis. Set in verdant rice fields, the Miftahul Huda school is the largest of its kind in west Java. More than 4,000 students come here to study the Koran. After surrendering my ID I was permitted to drive up to the executive office, where after a while a pair of surly youths dressed in black invited me to sit on the floor.

"Who are you and where are you from?" the younger man asked suspiciously.

The conversation was sparse. No, they do not engage in politics; students are not even allowed outside the school perimeter without special permission. Yet it was from here in 2017 that the first march on Jakarta was organised to demand Ahok's arrest.

Back in Bandung, I caught up with Jalaluddin Rakhmat, a member of parliament for Jokowi's main party platform, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP).

"Both Prabowo and his Muslim supporters suffer from delusions," he said in his humble home situated just north of the regional capital. "Prabowo thinks if he wins he can dump the Muslims. The Muslims in turn are using Prabowo to come to power."

It's a bit like the way Christian evangelicals think they are using US President Donald Trump.

Jalaluddin, who is from the small Shiite minority, is among those who fear the erosion of tolerance for diversity. "We Muslims who are with Jokowi stand for a different Islam: we don't want to take Islam as the basis of the state." For people like us, he said, "if we go to Prabowo we will find monsters".

The problem for Jalaluddin, and like-minded Indonesians anxious to shore up pluralism, is that Jokowi is widely regarded as having failed to deliver as a moderate. He has been soft on human rights and has pandered to the Islamic right. Many young people living in the Indonesia of tolerance and pluralism are too scared to vote for Prabowo but dislike Jokowi. They might spoil their ballots, or not vote at all.

Is there a way to reconcile these two Indonesias? While canvassing views I came across an interesting experiment in social development. A group of Muslim activists at Salman Mosque, which sits next door to Bandung's Institute of Technology, were looking for ways to harness Islamic teaching to progressive change.

"We're looking for local champions," said Salim Rusli, who runs Al Wakaf, an NGO attached to the mosque, which has a long history of student activism. These can be local ulama who use Islamic teaching to promote innovative thinking about mundane issues such as marketing vegetables or who foster constructive communication with local government.

This kind of grass-roots societal approach could also begin to build bridges across the religious divide that has opened in Indonesian society. But it will require political leaders like Prabowo to stop using Islam as a political weapon, or Jokowi to strengthen his leadership by framing a national narrative that more actively and effectively defends the tolerance of minorities.