TS

kolonel.bejo

(Jarang Dibicarakan) Nuklir Pakistan

In the mid-1970s Pakistan embarked upon the uranium enrichment route to acquire a nuclear weapons capability. Pakistan conducted nuclear tests in May 1998, shortly after India's nuclear tests, declaring itself a nuclear weapon state. Pakistan currently possesses a growing nuclear arsenal, and remains outside both the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).

Capabilities

Hans Kristensen and Robert Norris characterize Pakistan as having, "the world's fastest-growing nuclear stockpile." [1] According to the SIPRI 2013 Yearbook, Pakistan possesses between 100 and 110 nuclear weapons. [2] However, the International Panel on Fissile Materials concluded in 2013 that Pakistan possesses fissile material sufficient for over 200 weapons. Islamabad has stockpiled approximately 3.0 ± 1.2 tons of highly enriched uranium (HEU), and produces enough HEU for perhaps 10 to 15 warheads per year. Pakistan currently has a stockpile of 150 ± 50 kg of weapons-grade plutonium, with the ability to produce approximately 12 to 24 kg per year. [3] Plutonium stocks are expected to double as Pakistan brings more production reactors online at its Khushab facility. The Khan Research Laboratories greatly increased its HEU production capacity by employing more efficient P-3 and P-4 gas centrifuges. [4]

History

Establishing a Nuclear Program: 1956 to 1974

Pakistan asserts the origin of its nuclear weapons program lies in its adversarial relationship with India; the two countries have engaged in several conflicts, centered mainly on the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Initial steps toward the development of Pakistan's nuclear program date to the late 1950s, including with the establishment of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) in 1956. [5] President Z.A. Bhutto forcefully advocated the nuclear option and famously said in 1965 that "if India builds the bomb, we will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own." [6] After the December 1971 defeat in the conflict with India, Bhutto issued a directive instructing the country's nuclear establishment to build a nuclear device within three years. [7] India's detonation of a nuclear device in May 1974 further pushed Islamabad to accelerate its nuclear weapons program, although the PAEC had already constituted a group in March of that year to manufacture a nuclear weapon. [8]

A.Q. Khan's Contribution: 1975 to 1998

The Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, headed by Munir Ahmad Khan, focused on the plutonium route to nuclear weapons development using material from the safeguarded Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (KANUPP), but its progress was inefficient due to the constraints imposed by the nuclear export controls applied in the wake of India's nuclear test. [9] Around 1975 A.Q. Khan, a metallurgist working at a subsidiary of the URENCO enrichment corporation in the Netherlands, returned to Pakistan to help his country develop a uranium enrichment program. [10] Having brought centrifuge designs and business contacts back with him to Pakistan, Khan used various tactics, such as buying individual components rather than complete units, to evade export controls and acquire the necessary equipment. [11] By the early 1980s, Pakistan had a clandestine uranium enrichment facility, and A.Q. Khan would later assert that the country had acquired the capability to assemble a first-generation nuclear device as early as 1984. [12]

Pakistan also received assistance from states, especially China. Beginning in the late 1970s Beijing provided Islamabad with various levels of nuclear and missile-related assistance, including centrifuge equipment, warhead designs, HEU, components of various missile systems, and technical expertise. [13] Eventually, from the 1980s onwards, the Khan network diversified its activities and illicitly transferred nuclear technology and expertise to Iran, North Korea, and Libya. [14] The Khan network was officially dismantled in 2004, although questions still remain concerning the extent of the Pakistani political and military establishment's involvement in the network's activities. [15]

Pakistan as a Declared Nuclear Power: 1998 to the Present

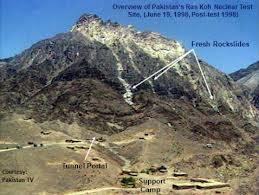

On 11 and 13 May 1998, India conducted a total of five nuclear explosions, which Pakistan felt pressured to respond to in kind. [16] Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif decided to test, and Pakistan detonated five explosions on 28 May and a sixth on 30 May 1998. In a post-test announcement Sharif stressed that the test was a necessary response to India, and that Pakistan's nuclear weapons were only "in the interest of national self-defense… to deter aggression, whether nuclear or conventional." [17]

With these tests Pakistan abandoned its nuclear ambiguity, stating that it would maintain a "credible minimum deterrent" against India. [18] In 1998, Pakistan commissioned its first plutonium production reactor at Khushab, which is capable of yielding approximately 11 kg of weapons-grade plutonium annually. [19] Based on analysis of the cooling system of the heavy water reactors at Khushab, Tamara Patton estimates the thermal capacity and thus the plutonium production capacity of Khushab II and Khushab III to be ~15 kg and ~19 kg per annum respectively. [20] Construction of a fourth plutonium production reactor at Khushab is ongoing and is estimated to be more than 50% complete based on satellite imagery analysis. [21] Patton estimates that "if Khushab IV has at least an equivalent thermal capacity as Khushab III, the entire complex could be capable of producing 64 kg of plutonium per year or enough fissile material for anywhere from 8–21 new warheads per year depending on their design." [22] Associated facilities and their associated security perimeters are also being expanded, including the plutonium separation facilities at New Labs, Pakistan Institute of Science and Technology, to reprocess spent fuel from the new reactors at Khushab. [23]

Islamabad has yet to formally declare a nuclear doctrine, so it remains unclear under what conditions Pakistan might use nuclear weapons. [24] In 2002 then- President Pervez Musharraf stated that, "nuclear weapons are aimed solely at India," and would only be used if "the very existence of Pakistan as a state" was at stake. General Khalid Kidwai further elaborated that this could include Indian conquest of Pakistan's territory or military, "economic strangling," or "domestic destabilization." [25] Because of India's conventional military superiority, Pakistan maintains the ability to quickly escalate to the use of nuclear weapons in case of a conventional Indian military attack. [26]

Disarmament and Nonproliferation Policies

Pakistan is not a signatory to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and is the sole country blocking the negotiations of the Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty (FMCT). Pakistanis argue that in the face of India's increasing conventional capability, it is unreasonable to expect Pakistan to cap is fissile materials production. Furthermore, they argue that the FMCT legitimizes India's fissile material stocks. [27] At the Conference on Disarmament (CD) in January 2011, Pakistan reiterated its opposition to the commencement of negotiations towards an FMCT. [28] While declaring its opposition to the FMCT in its current format at the CD in January 2010, Islamabad called for the CD's agenda to be enlarged to consider aspects of regional conventional arms control and a regime on missile-related issues, while also maintaining its opposition to a treaty that did not cover fissile stocks retroactively. [29]

In general, Pakistan's position on nuclear disarmament is that it will only give up nuclear weapons if India gives up its own nuclear arsenal, and in 2011 the National Command Authority "reiterated Pakistan's desire to constructively contribute to the realization of a world free of nuclear weapons." [30] However, given Islamabad's objective of balancing India's conventional military and nuclear superiority, Pakistan is unlikely to consent to a denuclearization agreement. [31] Islamabad has also consistently refused to sign the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), and from 2009 to 2010 official Pakistani statements indicated that even if India signed the treaty, Islamabad would not necessarily follow suit. [32]

Pakistan is a member of some multilateral programs, including the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism. Islamabad has also put into place more stringent export control mechanisms, including the 2004 Export Control Act and the establishment of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Strategic Export Control Division (SECDIV) to regulate exports of nuclear, biological, and missile-related products. [33] The Export Control (Licensing and Enforcement) Rules were published in 2009, and in July 2011 Islamabad issued an updated control list including nuclear and missile-related dual-use goods to bring its restrictions in line with those of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), and the Australia Group (AG). [34] Additionally, Pakistan has been involved in the U.S. government's Secure Freight Initiative through the stationing of systems at Port Qasim to scan containers for nuclear and radiological materials. [35]

Nuclear Weapons Security

The security of Pakistan's nuclear weapons has been of significant concern to the international community in recent years, with increased terrorist and insurgent violence and expanded geographical areas of the country under Taliban control. Senior Al Qaeda leaders have also expressed an interest in co-opting Pakistan's nuclear weapons. [36] Such developments increase the likelihood of scenarios in which Pakistan's nuclear security is put at risk. Since 2007, Taliban-linked groups have successfully attacked tightly guarded government and military targets in the country. Militants carried out small-scale attacks outside the Minhas (Kamra) Air Force Base in 2007, 2008, and 2009, and gained access to the site during a two-hour gunfight in August 2012. [37] Pakistani officials have repeatedly denied claims that the base, which houses the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex, is also used to store nuclear weapons, and a retired army official asserted that Pakistan's nuclear weapons are stored separately from known military bases. [38] However, several Pakistani nuclear facilities, including the Khushab facility and the Gadwal uranium enrichment plant, are in proximity to areas under attack from the Taliban. [39] Additionally, there have been some attempts to kidnap officials and technicians working at nuclear sites in western Pakistan, although it is not clear who was responsible or what their intentions were. [40]

Nevertheless, Islamabad has consistently asserted that it has control over its nuclear weapons, and that it is impossible for groups such as the Taliban or proliferation networks to gain access to the country's nuclear facilities or weapons. After 11 September 2001 and the exposure of the A.Q. Khan network, Pakistan has taken measures to strengthen the security of its nuclear weapons and installations and to improve its nuclear command and control system. [41] The National Command Authority (NCA), composed of key civilian and military leaders, is the main supervisory and policy-making body controlling Pakistan's nuclear weapons, and maintains ultimate authority on their use. [42] In November 2009, Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari announced that he was transferring his role as head of the National Command Authority to the Prime Minister, Yusuf Gilani. [43] The Strategic Plans Division (SPD) is the secretariat of the NCA, and is responsible for operationalizing nuclear doctrine and strategy, managing nuclear safety and security, and implementing the command and control system. [44]

Pakistan has also strengthened its personnel reliability program (PRP) to prevent radicalized individuals from infiltrating the nuclear program, although various experts believe that potential gaps still exist. [45] Pakistani analysts and officials state that they have developed their own version of "permissive action links" or PALs to safeguard their warheads, and have not relied on U.S. assistance for this technology. [46] Satellite imagery also shows increased security features around Kushab IV. [47] In recent years, the United States has provided various levels of assistance to Pakistan to strengthen the security of its nuclear program. [48] According to reports in April 2009, with the expansion of Taliban control in western Pakistan, Islamabad shared some highly classified information about its nuclear program with Western countries in order to reassure them of the country's nuclear security. [49]

Civilian Nuclear Cooperation

Pakistan has been critical of the U.S.-India nuclear cooperation agreement, but at the same time has periodically sought a similar arrangement for itself, a demand Washington has so far turned down. [50] In 2008 Islamabad pushed for a criteria-based exemption to the rules of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), which unlike the country-based exception benefiting only India could have made Pakistan eligible for nuclear cooperation with NSG members. Despite its reservations about the India special exception, Islamabad joined other members of the Board of Governors in approving India's safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in August 2008. [51] At the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington in April 2010, Islamabad again sought "non-discriminatory access" to civilian nuclear technology, while also offering nuclear fuel cycle services covered by IAEA safeguards to the international community. [52]

Recent Development and Current Status

In response to the U.S.-India deal, Pakistan has sought to increase its civilian nuclear cooperation with China. Under a previous cooperation framework China had supplied Pakistan with two pressurized water reactors, Chashma 1 and Chashma 2, which entered into commercial operation in 2000 and 2011 respectively. [53] In April 2010, reports confirmed long-standing rumors that the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) had agreed to supply two additional 650-MW power reactors to Pakistan, Chashma 3 and Chashma 4. [54] These reactors are currently under construction at the Chashma Nuclear Complex and will also be placed under IAEA safeguards. [55] Chashma 3 and Chashma 4 are expected to be completed by 2016 and 2017, respectively. [56] China, a member of the Nuclear Suppliers Group since 2004, did not pursue an exemption to NSG guidelines for Pakistan, instead arguing that Chashma 3 and 4 are "grandfathered in" under the pre-2004 Sino-Pakistan nuclear framework. [57] While the United States has consistently rejected this argument, the deal has been accepted as a "fait accompli" in international fora such as the NSG and the IAEA. [58] As of 2013, China and Pakistan are rumored to have an agreement for a fifth 1000MW unit at the Chashma Nuclear Complex. Details of any such agreement have not been made public. [59] While China argues that Chashma 3 and 4 are "grandfathered in," the fifth reactor, if it does indeed come to fruition, would be the third reactor built since China joined the NSG.

As of early 2014, the Pakistani government has begun a bid for three additional nuclear power plants, reportedly to be built in the Muzaffargarh district, Punjab province. At a cost of approximately USD 13 billion, this bid could enable Pakistan to meet its 2030 goal of generating 8,800 MW of nuclear energy to solve its chronic power shortages. [60

http://www.nti.org/country-profiles/...istan/nuclear/

============================================================

walaupun negara miskin tapi senjatanya bro

0

4.6K

15

Thread Digembok

Urutan

Terbaru

Terlama

Thread Digembok

Komunitas Pilihan